After the Deluge

By Nancy Rommelmann, October 25, 2024

ASHEVILLE, North Carolina — At 7:30 a.m. on Friday, Sept. 27, Chris Trusz was standing on one of the bridges spanning the Broad River in Chimney Rock. He wanted to get a photo. It had been raining steadily for 36 hours and the river was running 10 inches above normal. Trusz, who’d moved to the western North Carolina mountain town 18 months earlier, wasn’t worried; residents had been warned there might be a bit of flooding. He got his picture and walked up the hill to his home.

“Normally I have a sliver of a view of the river,” he said. “Now I’m looking and can see the river clearly.” By the time he got back to Main Street, the Broad was three times as wide and running 30 inches high. Within the hour, buildings had slid off their foundations, some taken down by the furious mud-colored current and disappearing completely.

“We were watching homes wash by, all kinds of debris,” said Trusz. Worse, he recalled, were the cars being carried away, some with their headlights still on.

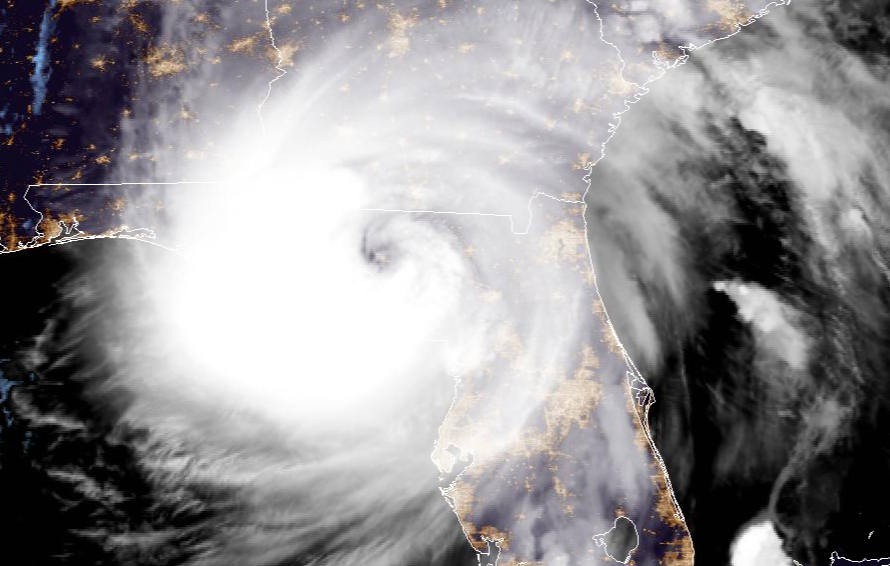

“I can’t unsee that,” said Trusz, three weeks after Hurricane Helene took down several western North Carolina towns, paralyzed the entire region, and killed at least 123, a number that will almost certainly rise and may prove unknowable.

It is one of several terrible unknowns the residents of western North Carolina now face. That they were unprepared for Helene is not on them – neither was the government nor anyone else. The “once in a thousand years” storm was not supposed to happen here, 500 miles from the Gulf of Mexico and 2,100 feet above sea level. There had been no local evacuation order even as the storm barreled their way. It would dump 30 inches of rain on western North Carolina and create up to 140-mile-per-hour winds. It would bring down untold thousands of trees. It would knock out the electrical grid, cell phone service, and the water supply all at once. In a matter of hours, it would obliterate the everyday security people felt, leaving survivors blinking into a new reality, wondering if they could or should rebuild lives in a place whose fragility had just been betrayed.

“If you live here or own a business, where do you go when it’s completely wiped out? I mean, how do you start over from that?” asked Trusz, a property manager for Airbnb who’d just found out the company was forbidding area rentals until June 2025 at least.

Further betrayal would come, during America’s overheated election season, from politicians, partisans, and conspiracists attempting to use the destruction and death caused by Helene to score political points. While mainstream news outlets suggested the area was being commandeered by armed right-wing militias, Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene was tweeting, “Yes they can control the weather” (no elaboration as to who “they” were).

Echoing a common complaint, Elon Musk claimed that “FEMA is not merely failing to adequately help people in trouble, but is actively blocking citizens who try to help!” Before long, Musk would instead be thanking Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg for “expediting approval for support flights.” Below the radar were the innumerable others stoking discord, including the person who tweeted at me, “Water Back on in Asheville NC. Feels like BLEACH on my skin. Very hot. Burning my face….” This just after he retweeted several racist memes and the claim that the death toll in Asheville was over 8,000.

Because of its unexpected and painful destruction, western North Carolina has become another symbol of America’s cultural divide. One side is the politicization of everything, as human suffering was quickly transformed into a partisan cudgel swung by party operatives and media outlets who fed the public versions of events that advanced their favored narratives. On the other side was the heroic story of people and government working together as best they could in cataclysmic circumstances to aid and comfort one another.

That second, hopeful story is what I found while reporting in and around Asheville last week. In a hotel with no running water, guests, some of whom had multiple trees fall on their homes, made do. While the scene could resemble a pajama party gone wrong, with people shuffling to the Porto-Sans in the driveway and choosing not to comment on the smell of body odor in the elevator, most folks showed concern for what their fellow travelers were going through. They left food and drink on a table in the lobby, next to a paper plate onto which someone had written “Take what you need.” They had neither the luxury nor desire to make political hay from their brethren’s misery. And when the taps turned back on, the water was clear if not yet potable, and when you washed with it, it did not burn.

Capitalizing on the misfortune of others is reprehensible, and no one I met in western North Carolina had the leisure time or the inclination to do so. Many are still without drinking water. Commercial districts have the same ghostly quality they had during COVID, and the shoulders of many roadways are piled with what was left of downed trees, the white oaks, maples, and pines that drew 14 million visitors a year, especially in late September and October, when the region blazes red and gold.

If many of those trees are now gone, what happens to the tourism economy and its $7.7 billion? What of Asheville’s major creative draw, the River Arts District, where floodwaters reached 27 feet and where what studio spaces remain have been taken down to the studs? Where do people find the courage, and the resources, to start again? And what if the thousand-year storm turns out to have a different schedule?

“I have childhood memories up there in Chimney Rock on Lake Lure, my granddaddy took me up there,” said Beverly Ramsey. “How do you rebuild something like that?”

Ramsey was driving to T-Birds, the bar she has frequented most days since Helene hit, not to drink but to see how she can help. The Weaverville lounge, usually known for its pool tables and karaoke, had been converted into a repository for donated goods, currently being organized by 25-year-old Alex Holt. Holt worked faster than someone running over hell’s half-acre, organizing the pet food and sleeping bags and propane tanks and maple syrup and other items brought on trailer trucks – so many that, 20 days post-Helene, they were backed up on Old Mars Mill Highway. How many were arriving a day?

“I couldn’t give you an exact number, they’re coming from Arkansas, Pennsylvania, Mississippi,” said Holt, who clearly had zero time to chat. “We’re just trying to meet everyone’s needs.”

“Can you imagine getting your period through all this?” Ramsey asked, sorting through a shopping bag a local woman had just dropped off, individual baggies holding six tampons and a two-pack of chocolate cupcakes.

Ramsey had been in Weaverville, a town of about 5,000 people 11 miles from Asheville, at her elderly mother’s home when Helene hit. As for how terrifying it initially was that morning: not very.

“I slept through it,” she said. Her main concern, when she woke up and saw the power was out, was being unable to make coffee. She decided to walk to a nearby Bojangles.

Forty-five minutes later she was back, the scene she encountered outside both impassable and making no sense. Dozens of big trees lay across the suburban street. Climbing over limbs and under fallen power lines, she came across three men using chainsaws to cut a hole in the fallen trees. Did they know what had happened? They did not; they had no cell service. Ramsey checked her own phone. No signal. Overhead, she heard the whomp whomp of a Chinook helicopter. What the hell was going on?

It was not until that night, when a neighbor used a power inverter to hook a car battery to his television, that Ramsey would begin to learn of the damage caused by Hurricane Helene. The flooding appeared to be the worst since The Great Flood of 1916 when the region experienced 26 inches of rain. Helene would dump 30 inches, or more than 40 trillion gallons, though Ramsey would not know as much for days; no one could, not with all communications cut, and roads crisscrossed with downed trees, and some washed away entirely. Other than by helicopter, there was no way in or out, and in some cases, people could not reach their closest neighbors, to say nothing of the outside world.

Help nevertheless got through. “That first day, people brought us gas, water,” said Ramsey, who let those who could not get home, or no longer had homes to get to, crash on her floor. Where some blamed the government for not immediately rushing to the rescue, Ramsey praised the self-reliance of her neighbors.

“Hillbillies and rednecks are a community. They want to talk about how Podunk we are and backwards. But no, we got this,” she said. “We need outside assistance, obviously. But we came together immediately.”

They mourn the deaths together, too. Ramsey mentions 11 members of the Craig family buried alive in a mudslide, and shows me the cover of a local paper, a photo of Alison Wisely and her two young sons, swept away, along with her fiance, when they left their car and tried to run for safety.

“And the farms, the water rushed out and took them down to the bedrock,” said Ramsey. “I mean, you don’t come back from that. That kind of property will never be farmed again. Not in our lifetime or even our children’s lifetime.”

While she has no idea when or whether her commercial cleaning business will reopen, Ramsey is optimistic about the future – and she isn’t.

“I don’t know that Asheville will be any different because it was already a tight community. Now as far as rebuilding places like Chimney Rock, I don’t know that that’s going to happen,” she said. “I have childhood memories up there. This is in the 70s, and very little has changed since then, as far as the aesthetics. So how do you rebuild something like that?”

Before the rebuilding, the clean-up. How much is complete and how much there is to go, three weeks post-Helene, is not possible to know. Asheville’s River Arts District looks as though it has undergone a bombing: two square miles of crumbled warehouses, brick piles, splintered lumber, and vehicles packed with mud from when the French Broad River, which runs parallel to the RAD, left the district underwater. The fate of the structures, many of them former mills and factories built around 1900, is unknown. What happens to a 120-year-old foundation that’s been sitting under 27 feet of water? Touring the district with Buttigieg on Oct. 17, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper struck a hopeful if vague note, saying the area would “come back” but probably “in a different way.”

Uncertainty continues as you drive east, on bridges until recently acting as catchments for debris and buildings packed with 12 feet of sludge, debris and more sludge pushed to roadsides and going on for miles. Everywhere, there are earthmovers, bucket trucks, linemen restringing electrical lines, water trucks bringing potable water – proof of life on a landscape that can otherwise appear post-apocalyptic, the town of Swannanoa leveled by the river of the same name, the town of Lake Lure sealed up tight.

Or nearly sealed. Lake House Restaurant was empty at 4 p.m. but for one bar patron when Rodolfo and Jose Hernandez came in for a bite. The brothers wore T-shirts that read, “S*E*R*T Swadley’s Emergency Relief Team,” the charitable arm of a chain of barbecue restaurants that makes it their business to get food to disaster zones.

“Brent Swadley, he bring a big, big kitchen and trailers from OKC. We get here last Thursday,” said Rodolfo, who is originally from Puebla, Mexico. He and Jose work as mechanics for the Swadley’s vehicles, though here, they also serve food to work crews. “The people are very happy to get real food, barbecue, steak, ribs, turkey, ham,” says Rodolfo. “Brent Swadley, he has a good heart.”

An ecosystem of good hearts formed post-Helene: the S*E*R*T team; the hundreds of trucks pulling up to T-Birds; the AI developer who, the day after the hurricane, made it his business to figure out how to find, bottle, and deliver drinking water; the Asheville bakery giving free fresh-baked pastries to patrons who left 20s in the tip jar; the seemingly limitless number of churches (“You hear the state sometimes referred to the as the prong in the Bible Belt,” said Beverly Ramsey, who is also an ordained minister) being of service, including the man in a “Don’t Let the Bad Days Win” shirt unloading pallets of bottled water and baby diapers; private citizens volunteering to go door-to-door to do wellness checks; translators helping non-English speakers fill out aid applications; community centers providing relaxation rooms to exhausted road workers; and the man who keeps a backpack of emergency supplies at-the-ready at all times who brought his 9-year-old daughter with him as he carried life-sustaining goods to people unable to escape their mountain homes, people for whom the surprise of a little girl brought its own kind of sunshine.

“Kids are just as motivated to help people as adults are,” the man said, adding that he did not bring his daughter on the darker missions, the ones he would not talk about.

As the people of western North Carolina get their bearings, many who swooped in to help will move to the next disaster; S*E*R*T was also in Florida, providing meals to those hard hit by Hurricane Milton. What “recovery” looks like is as yet unknown, and already there are frustrations, if not always a logical place to put them. People cannot be mad at the storm, or not with any hope of restitution. A storm will never say, “My bad.” And so people are mad, for instance, at their insurance companies, when they find out their policies do not cover flood damage.

“He’s having an incredibly hard time,” said one retired insurance agent, whose Asheville colleague was so besieged that she and other agents “formed a triage team so all calls went to a human voice. People needed to lay out their heart to someone on the other end of the phone.”

If for naught: The agent estimated that no more than 2% of policy owners had elected to carry flood insurance, and why would they? Western North Carolina is above the floodplain; the area had not catastrophically flooded since the Great Flood of 1916, also known as “the flood by which all other floods are measured,” a flood Helene out-measured, leaving property owners understandably desperate for someone to tell them there’d be money coming to repair their lives.

The best insurance could do, said the agent, was “get them a declaration form that says they were not [covered] and they could bring that to FEMA,” the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which, along with other government agencies, was experiencing its share of post-Helene consumer hatred, some of it whipped up by keyboard warriors claiming FEMA was holding “special meetings” to steal people’s homes and confiscate donations (assertions debunked by a local congressman), and that a North Carolina National Guard helicopter had deliberately sabotaged a distribution center (based on rotor wash having accidentally blown over some donated goods).

“There’s been a lot of rumors on social media in particular, and they’re not helpful in terms of our ability to help people,” said Mike Cappannari, external affairs officer for FEMA. Looking tired but composed amid the hundreds of storm victims milling through a Disaster Recovery Center set up on the campus of A.C. Reynolds High School in Asheville, Cappannari said FEMA had about 2,000 responders in the region, that it was still tough to get to some remote areas, and that in some cases the agency was working in concert with the Department of Defense to create points of distribution as close to disaster sites as possible. As for the wilder stories online, such as FEMA workers being chased down by truckloads of armed vigilantes, “You just try and fight through that,” he said. “Fortunately, over the past handful of days, we’ve seen not as much of that and are just trying to encourage people to register for assistance with us and see how we can help.”

Hanging out with a volunteer friend on another part of the Reynolds campus, it was hard for Kim Pierce to know what help she needed.

“I lost everything,” said Pierce, a slip of a woman who’d closed on a new East Asheville condo on Monday, Sept. 23. It was to be the first home she would live in without any of her six grown children, a ground-floor unit for which she’d paid cash, a place she envisioned riding out her semi-retirement with other residents, most of them over 60.

What she did not envision: waking up on Friday, Sept. 27, to find her new yard underwater. She did not envision moving a few cherished items to the trunk of her car for safety, only to watch her car sink. She did not envision falling into and scrambling out of the rushing Swannanoa River, taking refuge with neighbors she had never met, eating soup with them in a daze, and, because she was perhaps spryer and certainly more stubborn, getting the names, addresses, and prescription medications of these strangers and pledging to get to the nearest fire station to implore the fire crew to rescue them. Which she was doing when her sons-in-law showed up at her condo, found it underwater, and figured she was dead.

“When I showed up [at my daughter’s], she came screaming out of the house, she’s sobbing and is like, ‘Mama, I was writing your eulogy!’” said Pierce. “It was so hard to see my child so traumatized.”

Hard, too, to envision the future when the accumulation and plans of 60-plus years disappear overnight. “There is beauty that comes out of ashes. And I am experiencing it. I see it in little glimpses,” she said. “And then I go back into this fog of, I’ve lost everything.”

“Where do you put 30 inches of rain?” asked Chris Trusz, overlooking the Broad River, running today at normal capacity.

The question answered itself as he walked Main Street, past splintered furniture; car-sized clumps of dried mud, wood, and wire; crushed delivery trucks, dented refrigeration and a winery left precariously cantilevered by the storm.

“They’re going to have to bring in so much fill to get back up to where you possibly could rebuild,” said Trusz. “Most people will, because it’s a strong little town, but I can’t blame people for wanting to leave.”

While work crews continued clearing the roads, and while Trusz had nothing but goodwill for private and public sector efforts (“The community, the 101st Airborne, FEMA, everybody’s been here helping out,” he said, waving at several truckloads of National Guard), life in Chimney Rock has yet to resume, residents and business owners still figuratively rising to the surface. While the river was cleaning itself, those sorting through what was left of Gale’s Chimney Rock Shop – the clothing, souvenirs, and photos that had been inside the 77-year-old store now outside in sodden piles on a cold October afternoon – moved with deliberate slowness, trying to assess what could be saved from what was gone forever.

Leave a Reply